Monkey Research Brings Hope for Treating Alzheimer’s

There are many mysteries surrounding what causes Alzheimer’s, a progressive disease associated with changes in the brain that affect a person’s memory and mental functions. Clues necessary for improved treatments likely reside with monkey research.

More than 6 million Americans have this devastating disease, which means if you are reading this, you likely know someone who either currently is suffering or has suffered from it.

According to Mayo Clinic, Alzheimer’s patients may:

- Repeat statements and questions over and over

- Forget conversations, appointments or events, and not remember them later

- Routinely misplace possessions, often putting them in illogical locations

- Get lost in familiar places

- Eventually forget the names of family members and everyday objects

- Have trouble finding the right words to identify objects, express thoughts or take part in conversations

Truly heartbreaking symptoms begin to emerge in the more advanced stages of the disease. A parent may forget the name of their child, or that they ever had a child. Similarly, a husband or wife may forget the name of their spouse or that they were ever married to that person. Alzheimer’s takes an enormous toll not only on the patient but also on their close family members, loved ones and friends.

Scientists have long sought a way to delay or prevent Alzheimer’s, but a cure has so far remained out of reach. However, researchers have learned more about how the disease works and are likely to continue learning more with the help of animal research.

Like many human diseases, Alzheimer’s disease has a number of variations. Early onset Alzheimer’s is relatively rare and results from genetic mutations that rapidly produce proteins called amyloid and tau, which interfere with communication in the brain and cause neurodegeneration. The more common form of this disease, however, is late onset Alzheimer’s, which occurs with advancing age. About a third of people over 85 may have late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Unfortunately, the cause of late onset Alzheimer’s is complex and largely unknown.

Studies with mice have produced possible explanations about the origin of the neurodegeneration in humans with early onset Alzheimer’s. But studies with mice have not yet revealed what causes the more common, late onset form of Alzheimer’s disease, nor have they led to treatments that have prevented or substantially altered the course of late onset disease. Mice studies, while important, have produced limited information in this area for several reasons. First, the studies of Alzheimer’s with mice require genetic alterations based on early onset disease that might not apply to late onset Alzheimer’s. Second, mice have relatively little higher level “association cortex,” which is the focus of late onset Alzheimer’s disease research. Third, mice do not have long lives so they might not live long enough for the degeneration in late onset Alzheimer’s to emerge. Put simply, mice may provide some information, but may not be the best animal to study devastating effects of Alzheimer’s in elderly humans.

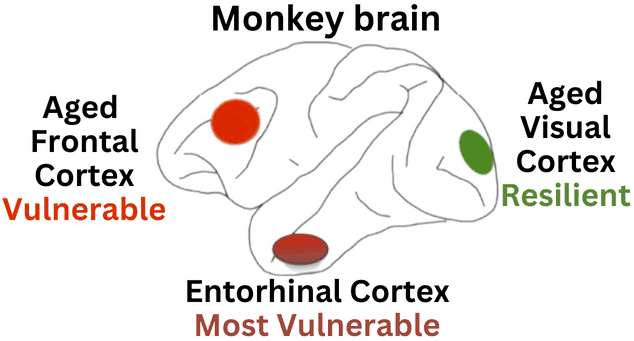

Figure 1: The monkey brain. Based on Fig. 6 from “Alzheimer’s-like pathology in aging rhesus macaques: Unique opportunity to study the etiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease” in PNAS

In contrast, rhesus macaque monkeys live longer, have an extensive association cortex (which integrates and organizes information and forms connections between other areas of the brain) similar to humans, and show cognitive decline with aging like humans. In the wild, rhesus monkeys usually die by age 15, but they can live more than twice as long in a research facility. Monkeys over the age of about 18 years are considered “aged.” Like humans they develop working memory deficits early in the aging process and recognition memory deficits at still older ages. They also develop changes in the brain that are remarkably similar to humans.

In humans, the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s occur in an area of the brain called the entorhinal cortex, which is needed for the formation of new, long-term memories. Nerve cells in the human entorhinal cortex begin to show abnormalities beginning even in middle age. Tau proteins accumulate and stick together, forming “tangles” inside cells in the brain, but do not afflict the primary visual cortex until very late-stage disease. When scientists examine the brains of very old rhesus monkeys, they see the same qualitative pattern of changes as seen in human brains. As illustrated in Figure 1, tau tangles that slow the ability to think first evolve in the entorhinal cortex in middle age (dark red circle) and then develop in the prefrontal cortex with more advanced age (bright red circle), sparing the primary visual cortex (green circle). Monkeys do not develop the extensive degeneration seen in more long-lived humans; however, many characteristics are very similar and provide the opportunity to see what causes and thus what might prevent Alzheimer’s in the aging brain.

One clue that has emerged is the finding that the entorhinal and prefrontal cortices in the brain show signs of toxic calcium build-up with advancing age, as proteins that normally bind calcium are lost with age. Excessive calcium levels can in turn drive Alzheimer’s pathology, in part characterized by the formation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Studying ways to reduce calcium accumulation in the entorhinal and prefrontal cortices of aging patients may be a promising direction for corrective treatment.

Advances in Alzheimer’s disease treatments so far are limited, and many elderly people still suffer from this form of dementia. The similarity of changes in the aging monkey brain and the aging human brain makes the monkey the most promising animal for studies of late onset Alzheimer’s disease, with the hope of developing treatments that could rectify the earliest stages of disease pathology and thus prevent future progression of the disease.

Monkeys in research are uniquely positioned to provide hope for the millions of Americans who suffer from this devastating disease.

Reference:

Amy F. T. Arnsten, Dibyadeep Datta, Shannon Leslie, Sheng-Tao Yang, Min Wang, and Angus C. Nairn. Alzheimer’s-like pathology in aging rhesus macaques: Unique opportunity to study the etiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2019, 116: 26230–26238

Consulting Scientist:

Professor Amy F.T. Arnsten, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.

Guiding Scientist:

Robert H. Wurtz, Distinguished Investigator Emeritus, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.

(Featured image credit: GSO Images / The Image Bank / Getty Images)